Sam Barrett traces his journey from research to recording

I almost laughed when I realised. Of course Cologne was the right place to record this repertory – in the Rhineland, where the songs we had reconstructed were collected together a thousand years earlier. It was also where my collaborators, the ensemble Sequentia, had begun experimenting with their innovative working methods. For my part, I had made the journey from Cambridge, home of the notated fragment that sparked our collaboration. So it was that in the summer of 2017, a scholar and a trio of musicians assembled to make a CD of some of the earliest surviving songs in the European medieval lyric tradition.

It all started some 1500 years previously in a cell in Pavia, where the Roman philosopher and statesman Boethius composed On the Consolation of Philosophy, awaiting his execution for treason. At the opening of his most widely read work, Boethius is visited in his cell by a personified figure of Philosophy, who is alarmed by the state into which he has fallen. Rebuked by her for his self-pity, the prisoner is gradually drawn into dialogue, exploring the ways of man, the role of Fortune, and the major questions of good and evil. In so doing, he is restored to his rightful mind, not just by Philosophy’s reasoned prose, but also by thirty-nine lyrics interspersed through the work.

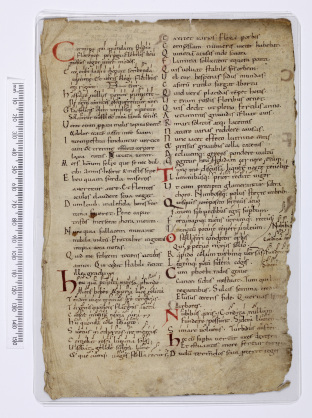

Reconstructing melodies added to the poems in the early Middle Ages was no simple task. A decade spent identifying notated manuscripts, analysing, writing and re-writing, had lead in 2013 to my publication of a two-volume study and transcription of the melodic tradition of the songs from the Consolation of Philosophy. The labour had felt Sisyphean at times, grasping at melodies that forever remained tantalisingly out of reach of established scholarly methods. No matter how much could be recovered about general procedures, the problem of a final leap into sound remained. Members of Sequentia proved ideal partners for experimenting with melodic realisations of mnemonic notations whose supporting oral traditions had died out. Initial, tentative meetings with Benjamin Bagby led to two further years of creative exploration, in which we were joined by harpist and singer, Hanna Marti, and latterly flautist, Norbert Rodenkirchen.

The first performance on an April evening in 2016 in Pembroke College, Cambridge, was revelatory. Melodies that had remained until then shadowy presences, were drawn into the light by Orphic voices accompanied by a lyre dug up from a nobleman’s grave, a harp crafted after a psalter illustration, and a flute hewn from swan bone. The performers’ artistry, refined through years of work in study and studio, had taken recovered fragments and transformed them. Listening to the elegiacs of Boethius’ opening lament, voices of my boyhood Latin teachers rang in my ears. The cathedral school at St Augustine’s Canterbury, the likely provenance of our notated leaf, did not feel so far removed after all.

The recording threw up new questions. How to capture and recapture the spontaneity of decision-making that characterised Sequentia’s live performances of these songs? Which versions to retain in a recording process that allowed for infinite erasure in pursuit of a definitive ‘take’? More songs were lost than retained as we talked, sang and played our way towards inscription of a newly memorized tradition. True to my training, I hoarded documentary evidence of the process, improvised notations and annotations, promising material for future study.

There followed the business of production, a new booklet for an old repertory. The Boethian verses laid out again in double columns: Latin, English, French and German. More words to explain the how and the why, to inform and educate another audience through marginal commentary. And all brought into a new material object, this time curated not at Canterbury, but by the record label Glossa thanks to a long-standing association between Sequentia and the Schola cantorum at Basel under its modern-day Master, Thomas Drescher.

Fast forward to today, the end of another academic year, and the launch day finally arrives. A culmination to the collaboration with Sequentia but also the beginning of a new chapter. Our CD is released alongside a new website to explain in another medium the what and the wherefore, and to open up to all-comers access to original sources, methods of reconstruction, and our restored versions in notated form. In search of feedback, impact (indubitably), but also to start afresh the slow process of revising and refining hypotheses, creating more and more deeply informed melodies. The dissemination of Boethian metra is underway again, to be received and transformed by all wishing to align themselves with a learned practice of reasoning and singing – a tradition brought to its first conclusion in a cell in Pavia at the end of one form of Europe and revived again on the brink of another.

This blog post first appeared on the Music@Cambridge Research Blog.